Justin Wiggins talked to Charlie in May 2025.

Charlie Cobbinah is a doctoral researcher and fellow of the Wits-Edinburgh Sustainable African Futures (WESAF) Doctoral Programme, an interdisciplinary program from the partnership between The University of Edinburgh and The University of the Witwatersrand. His research focuses on exploring the intersections between decolonization, higher education, and sustainable development in the context of Africa. Currently, his work aims at exploring the ways and the extent to which decolonial discourses are reinventing the self-reflexive identity and institutional role of African universities in advancing sustainable African futures.

Charlie Cobbinah is a doctoral researcher and fellow of the Wits-Edinburgh Sustainable African Futures (WESAF) Doctoral Programme, an interdisciplinary program from the partnership between The University of Edinburgh and The University of the Witwatersrand. His research focuses on exploring the intersections between decolonization, higher education, and sustainable development in the context of Africa. Currently, his work aims at exploring the ways and the extent to which decolonial discourses are reinventing the self-reflexive identity and institutional role of African universities in advancing sustainable African futures.

As an aspiring professor of African Development, Charlie is actively engaged in discussions on African sustainability and knowledge production initiatives, particularly in the context of higher education institutions across Africa. He has contributed to various initiatives and projects aimed at rethinking colonial legacies in African higher education and cultural institutions and fostering interdisciplinary approaches to knowledge production. Beyond academia, Charlie runs a social entrepreneurship program that empowers teenagers through education and leadership training.

As an invited guest at the DeCoGLAM event on 7 May 2025, Charlie chose the topic Whose Story? Critical Analysis of Primary Sources for Decolonized Curricula. Justin Wiggins from our team asked some additional questions.

What was an event in your life that inspired you to become passionate about decolonisation?

I wouldn’t call it a single event, but rather a lived experience. While several factors have contributed to my passion for decolonisation, one major influence has been the educational systems I encountered growing up in Ghana. From an early age, I absorbed ideas and constructs that felt significantly detached from my own context. This disconnect—and the dissatisfaction it brought—grew as I progressed through the academic ladder. However, during my postgraduate studies, my exposure to the discourse of decolonisation solidified my passion. I finally reached a point where I could name the dissatisfaction I had long felt and envision the possibility of change. Since then, through learning and being inspired by other leaders in the field of decolonisation, it has become a lifelong passion.

What does decolonisation mean to you?

To me, decolonisation means reimagining what our world could have been—and still can be—without the historical and enduring impacts of colonisation across many regions. Colonisation, in my view, has privileged only one way of knowing, being, and holding power. Decolonisation, therefore, is about transforming that dominant lens and making space for diverse worldviews, identities, and systems of knowledge.

From your time spent in academia, would you say that steps toward decolonisation have made good progress in society?

As an emerging scholar, I deeply appreciate the work of those who have contributed to the development of this field. Despite the many challenges that accompany this discourse and praxis, there has been significant progress—especially in recent years, following movements such as South Africa’s #FeesMustFall and other global “fallist” movements. We are now seeing academic institutions approach decolonisation with a renewed sense of urgency and commitment, and this is having a tangible impact—particularly in the growing emphasis on social justice.

What are some good resources for helping people understand the importance of decolonisation?

This is a tough one. Decolonisation is a vast and multi-layered field with diverse perspectives, so it’s difficult to narrow it down to just a few resources. However, I would recommend some foundational texts like The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon and Decolonising the Mind by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Additionally, there are insightful podcasts and online lectures that unpack the subject in accessible ways, depending on one’s level of familiarity.

In your current field of study, what do you hope to achieve through advocating the importance of decolonisation?

I am passionate about the future of (higher) education and hope to contribute to the reimagining of educational institutions in Africa and beyond through decolonisation. I believe that decolonising our institutions of learning is a powerful pathway toward reimagining our people, our communities, and the broader world—and ultimately, building a sustainable future.

What are some challenges with decolonisation in the 21st century?

That’s an interesting question. While decolonisation offers immense opportunities today, there are key challenges that must be addressed. Two major ones are: (1) the deep-rooted colonial legacies that remain embedded in our institutions and societal structures, and (2) the risk of tokenism and symbolic gestures that dilute the true transformative goals of the decolonial project.

Who are some poets, musicians, artists, or mentors that have inspired you on your journey in advocating for decolonisation?

I’ve been inspired by a number of individuals—both past and present. Among them, Kwame Nkrumah stands out the most. His ideas around decolonisation, Africanisation, and Pan-Africanism—though not without critique—represent, to me, the promise of a liberated and self-determined future for the African continent. Alongside Nkrumah, I also draw inspiration from contemporary thinkers and scholars such as Toyin Falola, Achille Mbembe, and Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, whose work continues to shape the decolonial discourse today.

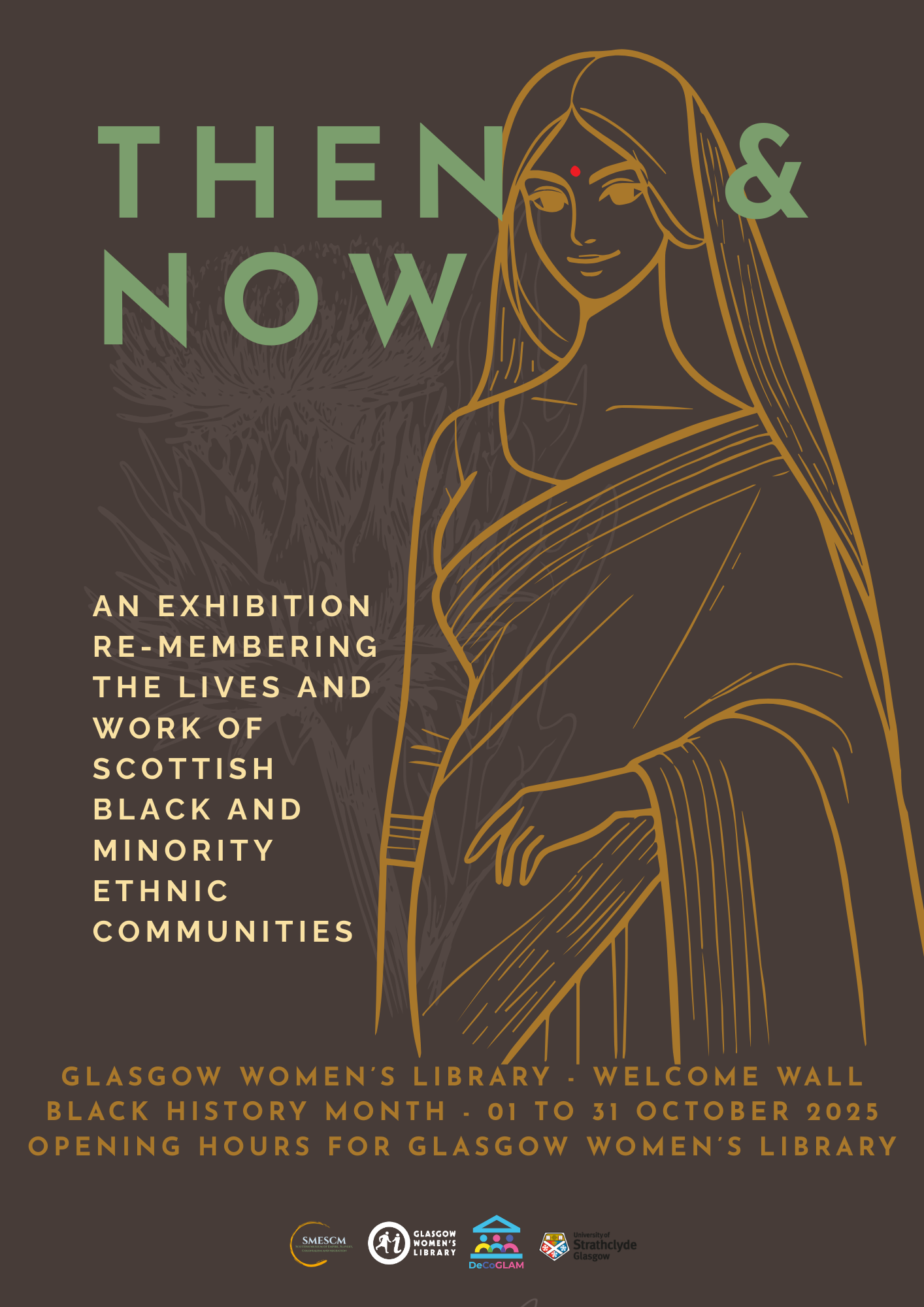

The exhibition Re-membering the Lives and Work of BME Scottish Communities(1–31 October) will be hosted by Glasgow Women’s Library and is part of the Black History Month supported by the Glasgow City Council. You are welcome to explore the exhibition – it does not need a registration!

The exhibition Re-membering the Lives and Work of BME Scottish Communities(1–31 October) will be hosted by Glasgow Women’s Library and is part of the Black History Month supported by the Glasgow City Council. You are welcome to explore the exhibition – it does not need a registration!

After graduating in Chemistry from the University of Warwick, I spent a year doing VSO in Kathmandu, Nepal. After that ‘Information Science’ seemed an interesting career move and I did an MSc in Information Science at City University. After that I worked in a wide variety of organisations, including industrial consultancy, the electricity industry, and a pharmaceutical company. I then combined child care with a variety of part-time work. After running a College of Nursing library for a couple of years, I took the chance of a research post working for, but not at, Aberystwyth. I started lecturing at Aberystwyth in 1995, and became a Senior Lecturer in 2000. Since early 2009 I have focused on research work.

After graduating in Chemistry from the University of Warwick, I spent a year doing VSO in Kathmandu, Nepal. After that ‘Information Science’ seemed an interesting career move and I did an MSc in Information Science at City University. After that I worked in a wide variety of organisations, including industrial consultancy, the electricity industry, and a pharmaceutical company. I then combined child care with a variety of part-time work. After running a College of Nursing library for a couple of years, I took the chance of a research post working for, but not at, Aberystwyth. I started lecturing at Aberystwyth in 1995, and became a Senior Lecturer in 2000. Since early 2009 I have focused on research work.

Charlie Cobbinah is a doctoral researcher and fellow of the

Charlie Cobbinah is a doctoral researcher and fellow of the